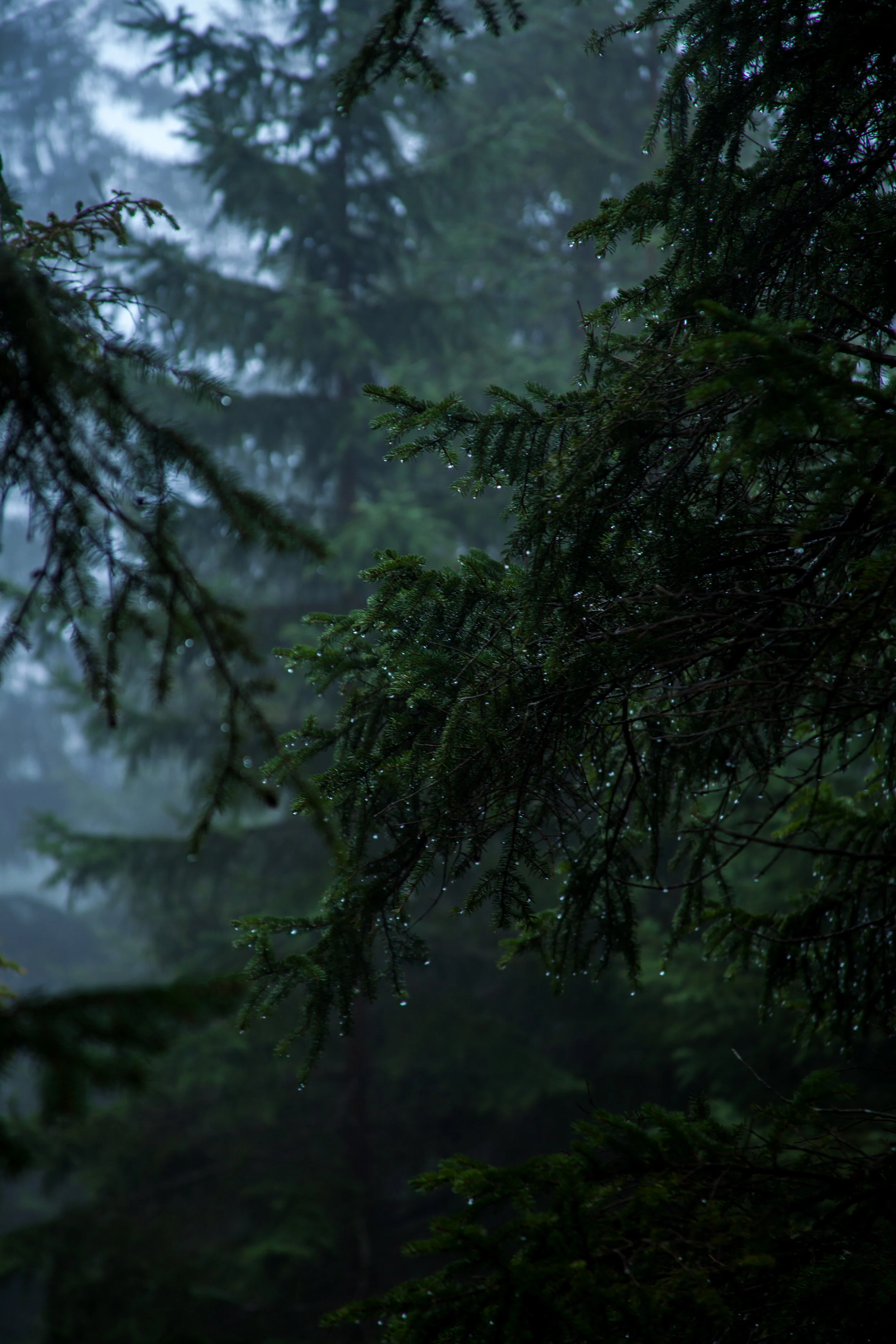

Juniper is a native North American evergreen tree that resides in the mountains and high desert. Sierra juniper (J. grandis) is the main juniper species of the Sierra Nevada mountain range, though J. communis and J. occidentalis can be found. Sierra juniper trees are amongst the oldest plants in Tahoe, some that are 1,000 years old. These beauties have adapted to thrive in a range of elevations from 3,000 to 10,000 feet. J. grandis can be found locally from Desolation Wilderness to Truckee, and J. communis and J. occidentalis are scattered from Tahoe to the Nevada desert. Juniper trees are most easily identifiable by being smaller and bushier than many nearby conifers. Typically they are found on rocky and open terrain on northern slopes. Further into the North Eastern high desert of Reno, they thrive and/or near sagebrush communities, where the low brush serves as shade for germinating seeds. These seeds or “berries” are used in a wide range of products from gin to medicine to skincare (ACHS, 2018; U.S. Department of Agriculture & Forest Service, 2019; Plants of the Tahoe Basin, 1999).

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture & Forest Service (2019), juniper berries are not actually berries at all, they are female cones. You will only find juniper berries on female trees that are between 20 to 70 years old. Juniper berries take 1-3 years to ripen; unripe berries are green and they ripen to a purple-blue color. The berries survive through the winter, making them a strong, hearty, year-round backcountry tea or culinary ingredient. They can be sweet and pleasant to bitter and spicy depending on the stage of the berry. Ripe berries can be eaten off the tree, 5-6 berries brewed into a tea, or in our case, fresh berries are distilled into a woodsy-piney-nutty medicinal aromatic essential oil. The oils are more abundant before they fully mature due to the increased resin production before full maturation (ACHS, 2018).

Juniper was considered sacred by may groups of indigenous people. People have been collecting the wood for its aromatic smoke for millennia. Among 70 wooden artifacts were preserved inside the tombs in 500BCE, 4 were made from juniper trees. When burned, juniper releases a rich turpentine perfume, which is important for Tibetan Buddhist ceremonies today. In European countries, the bark is burned in hospital rooms to purify the air. Juniper berries were used in baths as early as 1311 as an anti-inflammatory for itchy skin and allergic reactions. By the 15th century, juniper berry was used as antibacterial for treating compromised skin (American Botanical Council, 2003, NMD, 2019).

Juniper berries yield .5 to 3.2% essential oil depending on environmental variables. The oil contains antiseptic, antibacterial, and antioxidant monoterpenes alpha-pinene (20-50%), cadinene (10%), limonene (5-9%), myrcene (8.5%), borneol (8%), caryophyllene (7.2%), germacrene (7%), and small traces of sabinene, beta-pinene. The berries contain glucose, fructose, tannins, bitters, flavone glycosides, resin, wax, flavonoids, tannins, alkaloids, diterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and vitamin C (ACHS, 2018; NMD, 2019; Antioxidants, 2014).

Therapeutic qualities